Not meant for warmth and fuzzies

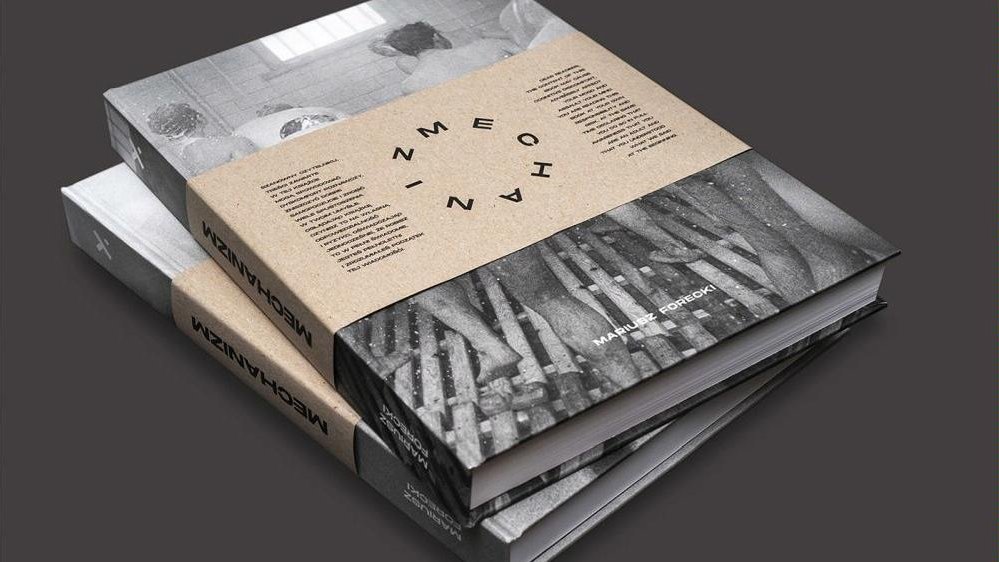

"Mechanism includes photos from Margaret Thatcher's 1988 visit to Warsaw during which the PM stopped at the Hala Mirowska market to pick up tomatoes, cucumbers and apples. I found the occasion to be a perfect opening for my book, an occurrence that symbolically influenced the events that subsequently unfolded in Poland", says Mariusz Forecki about his latest book of photographs: Mechanizm. Polska 1988-2019.

Your book Mechanizm is not quite - uhm - pleasing.

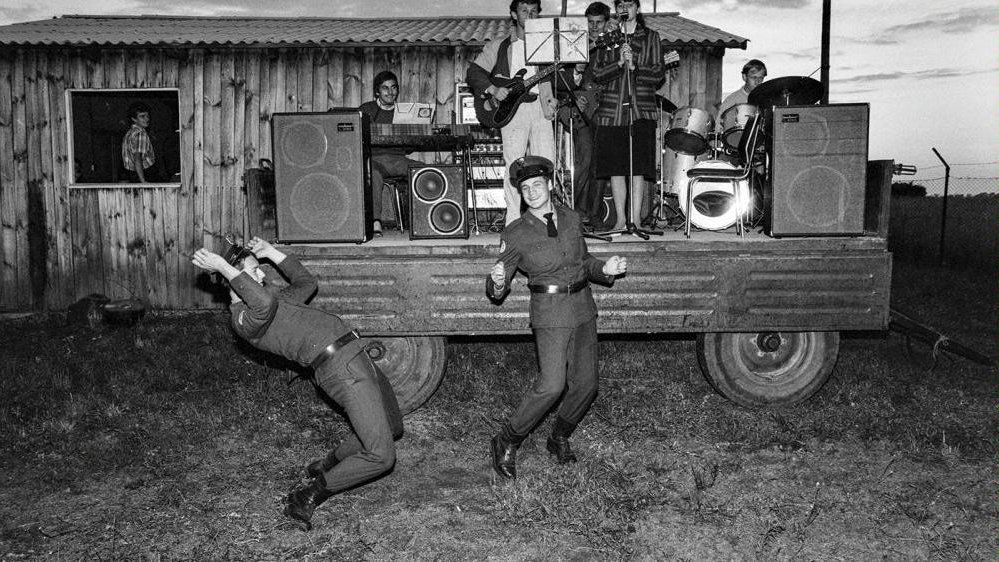

Physically, this book was meant to be one big heavy volume. Even the dust jacket advises viewer caution. Mechanizm... will not make you feel warm and fuzzy inside or ponder on what a marvellous world, and certainly not what a cool country, we live in. I fully intended to deliver a rough and jarring experience.

So that is the effect you were going for? Were you trying to debunk the claim that Poland is a wonderful country?

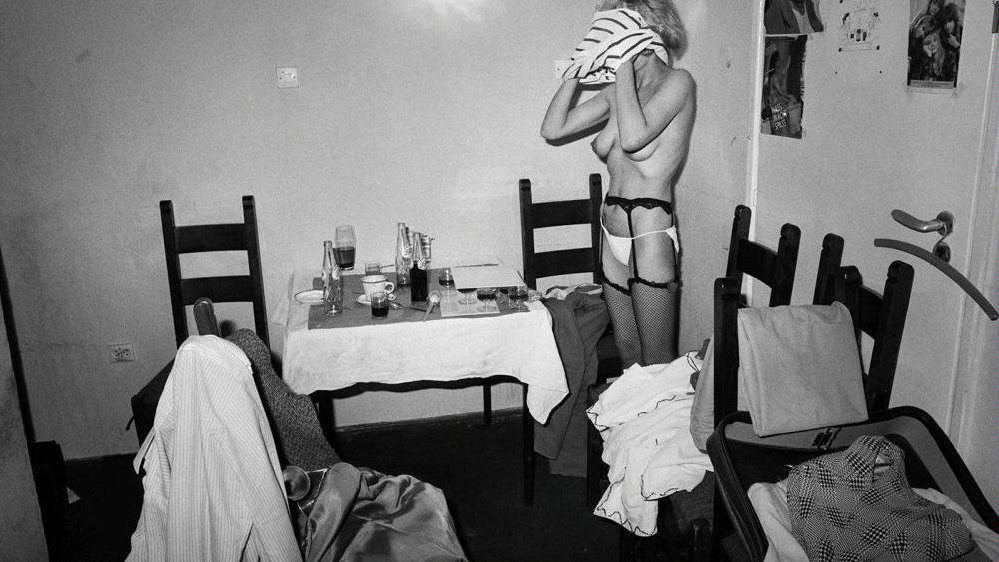

The unsightly harsh quality of the book's physical form is a good match for its content. I never cared for portraying the nice and the agreeable. I think my approach is more honest. In documentary photography, the "nice" can often stifle the message as the viewer becomes caught up in the beauty, colours and arrangements. The tendency is to leave out all ugliness or show it with great reluctance. I strived to take the alternative route of depicting the coarse and the impure. Even the impure though can be embraced - many people liked those times very much no matter how grim they found them to be.

How do you mean that?

Those days were friendlier in many ways. Despite their limited means, people were kinder to each other. As nobody knew how things should be done, we often groped in the dark for solutions making connections with other people in the process.

Today we are watched closely and judged every step of the way. Since your phone is on (pointing to my smartphone) - someone can spy on us and find out where you are and who you are talking to. Such surveillance is terrifying and hard to accept.

Were people more likely to let you take their pictures back in those days?

This is a completely different matter. Wouldn't you agree that today's laws are very strict about what one can photograph, leaving us with very little that can actually be shown? It may seem we are free to do as we please but just try doing it! In those days, freedoms may have been curtailed but photographers actually enjoyed more liberty than they do now. You could do many things without having to worry about liability. As a result, we can now see images from places that would be very difficult if not impossible to photograph today.

The people you portrayed seem to have had little idea of how they would end up looking in your photos. Today, we are more aware of the impact that images have and of the lines we draw between what we do and do not allow.

This is beside the point. People then would see themselves in the pictures and simply accept them. If documentary photography were to concern itself with producing flattering photos, it would churn out fashion, makeup and image magazines featuring celebrities. What I wanted to show was an unadorned, ungroomed world of people without makeup. Another good reason why people in those days were not camera-shy was the absence of hate speech, Facebook and global threats. Images circulated very slowly.

Did you seek out the ugly?

Far from it! What I really wanted to convey were the impressions and emotions I felt at that time. Not only the joy but also the simplicity and cragginess, all of which sticks out all the more when shown today, contrasted with our world. I wanted to show people's flair in starting their own businesses and making their way in a world in which many things were only just taking off the ground. It always takes a lot of tinkering and tweaking to develop something new. I wanted to chronicle the time when these processes were still in the bud.

Why are you having the book published now?

I feel that it took me all these years to realise the mechanisms and see what has changed and what has been re-evaluated in Poland. Earlier, such changes were hard to spot and capture - too little time had passed and one couldn't distance oneself from them properly. My story in Mechanizm ends in 2019 with the final photo I took in June of that year. That final photograph depicts a man sporting a wing tattoo on his back. With the wing already in place, the question was whether we would be able to use it to fly.

When did it first occur to you that you could tell the tale of transition with a book of photographs?

A while ago. In a way, everything I photograph is alike. I'm into social engineering and how people and communities evolve. I have already released two books on the subject: W pracy (At work) in 2010 and Człowiek w ciemnych okularach (A man in dark glasses) in 2016. The latter concerns the historic process of building a coherent Russian society. As I sifted through my negatives from the 1980s and "90s and saw what those times were like, the story told in Mechanizm came to me very clearly - it almost seemed easy to tell.

When you took the photos, your thoughts must have been very different from what they are now as you look at them from today's perspective.

For a long time, in my work, I have been acting on impulses that I haven't yet turned over in my head, responding to emotions and things that suddenly moved me. This is how I photographed things when I first started and how I do it today. This consistency of style actually allows me to compile images from many periods and piece them together into a consistent whole.

What did you learn while studying at university? Did your studies validate your work philosophy?

I haven't begun formal photography studies until 2005 when I was already a seasoned artist. At the time, I found myself missing an inspiration to gain new insights and further my progress. I then happened to come across students from the University of Opava who were visiting Poznań to display their work. They included Vladimír Birgus and Jindřich Streit. Right there and then, in my early forties, I felt that signing up for a course of studies would be a good idea. I enrolled in an undergraduate programme, got my B.A. and went on to pursue a master's degree. I am currently a doctoral student at my alma mater.

Have the studies changed anything in your approach?

They gave me a whole new perspective on what I had been doing. It was like climbing a mountain. You look down and notice cities all around that connect with each other. Every now and then though, your view is obstructed by clouds. Being able to see things from this vantage point helps you notice them and discover... mechanisms.

Mechanizm. Polska 1988-2019 (Mechanism. Poland in 1988-2019) is available in the Pix.House bookshop at ul. Głogowska 35, Poznań or online at https://pix.house/produkt/mechanizm_02/

Mariusz Forecki, documentary photographer, member of the Association of Polish Artistic Photographers, involved in multiple projects chronicling Poland's transition post-1989. He has authored a number of books and received numerous awards at press photography competitions.

translation: Krzysztof Kotkowski

© Wydawnictwo Miejskie Posnania 2020

See more

From One Celebration to Another

Christmas Markets and Fairs with Attractions

Truly Festive Vibes