Alma Mater Posnaniensis

It is hardly an exaggeration to say that 7 May 1919 was one of the most momentous dates in the history of the town of Duke Przemysł. The prestigious status of a university town, which Poznań gained on that day, resulted in rapid growth throughout the 20th century. Thus, the dreams of many generations of patriots, and social and organic work activists were spectacularly fulfilled. All of them worked tirelessly against terrible odds under the Prussian partition to preserve the national identity of Poznań and Wielkopolska, their sights set on establishing an institution of higher education that would produce the future Polish intelligentsia. The University's first chronicler, Prof. Adam Wrzosek, said that the many years of efforts to establish a university in Poznań that were undertaken in the 19th century by Hieronim Zakrzewski, Wojciech Lipski, August Cieszkowski and Karol Libelt, and that were invariably thwarted by the Prussian occupant, could not be successful until "the German power suddenly cracked, offering Poland a golden opportunity to regain its freedom."

In anticipation of this eagerly-awaited moment, another attempt to found the university was made by Prof. Heliodor Święcicki, President of the Poznań Society of the Friends of Sciences. It was through his efforts that, almost in the epicenter of the revolution that flared up in Germany, and immediately engulfed Poznań in the autumn of 1918, the inaugural meeting of the founding committee of the Polish university in Poznań was convened on 11 November of that year. On that day, the "founding fathers" of the Poznań Almae Matris gathered in the building of the Poznań Society of the Friends of Sciences. They were Prof. Heliodor Święcicki, the philosopher Dr Michał Sobeski, Rev. Stanisław Kozierowski from Skórzewo and the archaeologist Dr Józef Kostrzewski, who was appointed the secretary of that body. During the meeting, a fateful decision was made to set out on creating a department of philosophy. Postulates were put forward to additionally establish the faculties of medicine and law. An agreement was also reached on the future professorial salary, which was set at 10,000-15,000 marks for full professors. Finally, those present committed to work toward the very ambitious goal of "having the university opened by April 1919".

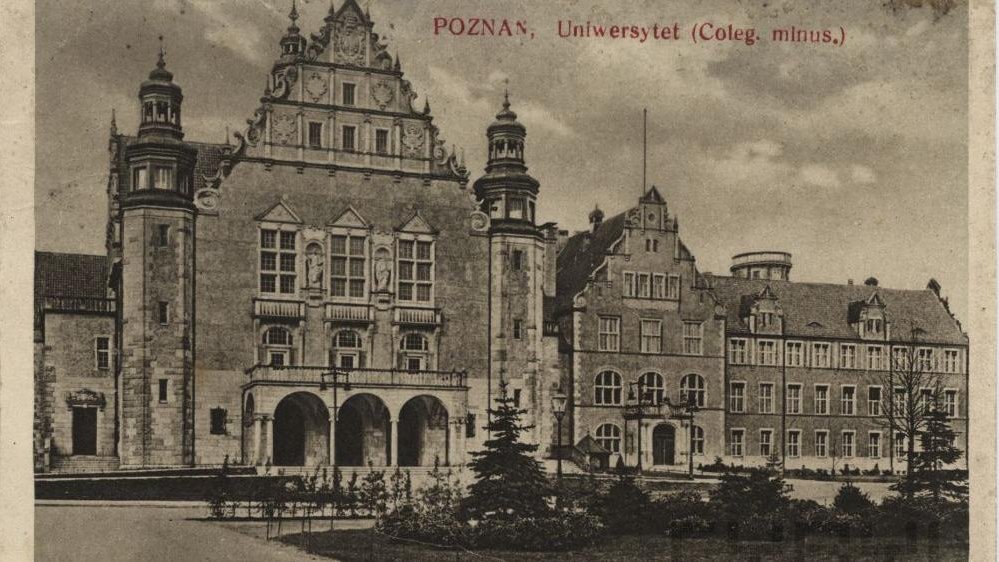

Six long weeks before the outbreak of the Wielkopolska Uprising, the University Commission made a strenuous effort to successively lay the groundwork for the future university, largely by establishing faits accomplis. Prof. Święcicki displayed boundless energy, especially in his battle to secure physical resources for the university and hire its faculty, in part through spectacular transfers of professors from Kraków and Lviv. Above all, he succeeded in averting the "threat" of having a Polish university set up in Gdańsk, this idea having had the potential to shatter Poznań's dream of academic prominence for years to come. The Commission's meetings, which were held every few days, produced their most tangible effects in early 1919. Under the unfortunate name of the Piast University, the institution (which was still under construction) was not only given the impressive buildings of the Royal Academy (Collegium Minus), the Imperial Castle (Collegium Maius) and the Library of Emperor Wilhelm I (University Library) to serve its needs, but also the favour and general organisational support of the Commissariat of the Supreme People's Council and the Warsaw Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Education.

This massive effort quickly produced concrete and lasting results. One of them was the inaugural meeting of the Faculty of Philosophy on 4 April 1919, during which Prof. M. Sobeski was elected the Faculty's first dean. On the following day, the same assembly unsurprisingly elected Heliodor Święcicki to serve as the first rector. Over the next month, a second department - one of law and economics - was established. The long awaited inauguration of the Polish university took place on 7 May 1919.

A highly elaborate university inauguration began with a solemn Holy Mass in the cathedral, celebrated by Archbishop Edmund Dalbor, and attended by all of Poznań's highest-ranking officials: members of the Commissariat and the Bureau of the Supreme People's Council, Gen. Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki, President Jarogniew Drwęski, and also "Minister of the Enlightenment" Jan Łukasiewicz, sent there from Warsaw, representatives of the University of Warsaw and the University of Lviv, the President of the Polish Academy of Learning, Kazimierz Morawski of the Jagiellonian University, and many others.

In the Cathedral, a capacity crowd, which included the "the newly-enrolled students of the Piast University", listened to a sermon by the prelate Fr. Stanisław Łukomski. A procession of many thousands, headed by an orchestra and a troop of scouts, then marched down ul. Chwaliszewo, ul. Wielka, Stary Rynek (Old Market Square), ul. Nowa, Plac Wolności, ul. Kościuszki, ul. Mielżyńskiego and ul. Święty Marcin, to finally arrive at the former imperial castle. There, in the former throne room, Archbishop E. Dalbor, Supreme People's Council Commissioner Adam Poszwiński, Rector H. Święcicki and Minister J. Łukasiewicz, as well as a representative of "Piast University youth: P. Mikołajczak" and Dr Ludwika Dobrzyńska-Rybicka, member of the academic association Universitas, addressed a crowd of over a thousand. Rector H. Święcicki turned directly to the young people: "Young friends, you have gathered here today not only to acquire an education in the academic sense of the word but also, and no less importantly, to learn how to be good citizens of your country, as you are the future apostles of our holy cause and the hope of our homeland". Minister Łukasiewicz followed with what amounted to a concise outline of the university's programme and its key objectives: "The Piast University is to replace Berlin and Wrocław for the Polish youth. Let it not only replace, but also exceed German universities. Let it provide students with knowledge imbued with the national spirit. [...] Let young people proudly bear the banner of science and spread culture in the westernmost regions of the Republic. "

In the afternoon, a big banquet was held in the White Hall of the Poznań Bazar building, in honour of the officials and other guests. The atmosphere was conducive to raising a "series of toasts." The extensive inauguration programme was made complete by an evening ceremony in Teatr Polski. From its stage, the historian Prof. Kazimierz Tymieniecki delivered an outstanding lecture on "The history of Polish universities". Afterwards, the theatre audience heard excerpts from "Przedświt" ("Predawn") by Zygmunt Krasiński, the piece "Do mojego grajka" ("To my musician") by Teofil Lenartowicz, and finally saw "Warszawianka" ("The Song of Warsaw") by Stanisław Wyspiański. However, there was no time for lengthy celebrations as the "fledgling university" was to open its doors to students as soon as 12 May 1919, and there was no shortage of various organisational challenges to tackle.

In the first full academic year of 1919/1920, the Piast University, which the Senate had just (on 24 June 1924) renamed the University of Poznań, admitted ca. 1 800 credit and auditing students, many of them struggling to secure adequate accomodation and sustenance. Not without reason, the local papers constantly "implored the honourable residents of Poznań" to contribute by "renting furnished rooms to students". Not unlike other institutions of higher education in the Second Polish Republic, the university was available primarily to young people from wealthy families. Admission fees, tuition, health care and other charges added up quickly, while dormitories and scholarships were always in short supply. All this notwithstanding, enrolment at the University of Poznań grew steadily, reaching 5,500 by 1933, which was a huge number for the Second Polish Republic. A steep rise was also seen in the number of departments, which grew to five (Philosophy/Humanities, Law/Economics, Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Agriculture/Forestry, Medicine), and in the number of research faculty members. Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, the latter numbered 550, including nearly a hundred ordinary professors, among them such prominent scholars as Florian Znaniecki, Antoni Jurasz, Edward Taylor, Adam Skałkowski, Adam Wodziczko, Roman Pollak and Zdzisław Krygowski.

It did not take long for the University of Poznań to become an integral part of the city, and, next to Pewuka: the General National Exhibition, Poznań's key calling card during the Second Polish Republic. The University drew people from the entire country, sparking scientific, cultural and social activity and increasing the numbers of scientific associations, magazines, events and initiatives beyond what can reliably be assessed today. As reported somewhat spitefully in the Dziennik Poznański daily, all this was achieved "in spite of malicious comments that resulted not as much from disapproval as they did from the ignorance of our community and that insultingly labeled our district the Polish Boeotia".

Vivat, crescat, floreat!

Piotr Grzelczak

translation: Krzysztof Kotkowski

For more, see: 100lat.amu.edu.pl

© Wydawnictwo Miejskie Posnania 2019

See more

From One Celebration to Another

Christmas Markets and Fairs with Attractions

Truly Festive Vibes